The Global Language: From Latin to Artificial Intelligence

How humanity's lingua franca has evolved throughout history — and why AI translation may render the very concept of a "world language" obsolete

Executive Summary:

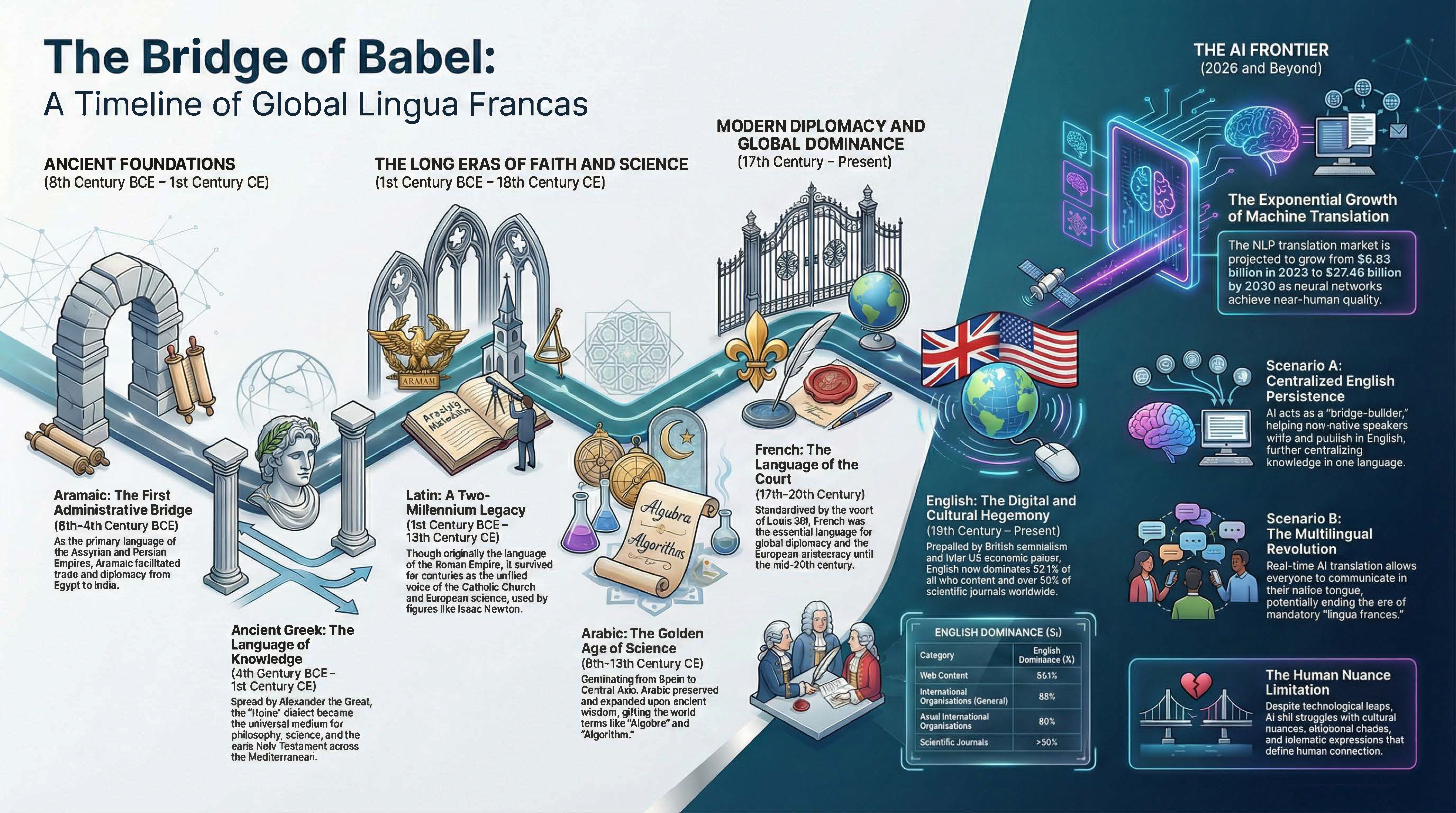

For millennia, humans have sought ways to overcome language barriers. Today, we stand on the brink of a revolution: AI translation technologies promise to make the institution of a global language obsolete. English currently dominates with 1.5 billion speakers (only 25% native), 85% of international organizations, and 52% of web content. Meanwhile, the machine translation market is projected to reach $23.5 billion by 2032, growing at 12-25% annually. This article traces the evolution of global languages from Aramaic to English — and explores what comes next.

The Evolution of Global Languages: A Historical Overview

Throughout history, the rise and fall of lingua francas has followed a consistent pattern: languages of power become languages of communication. From ancient empires to modern technology, each global language reflects the geopolitical reality of its era.

Aramaic: The First Global Language (8th–4th Century BCE)

The history of global languages begins not with English, nor even with Latin. Aramaic became the first truly international language during the 8th to 4th century BCE, during the Assyrian and Persian empires. It served as the language of trade and diplomacy across a vast territory stretching from Egypt to India. Jesus Christ spoke Aramaic, and the language survives to this day in some Middle Eastern communities.

Why Aramaic? The answer is simple: it was the language of those who held political and economic power. The Persian Achaemenid Empire spanned enormous territories, and Aramaic served as the administrative language connecting its numerous peoples.

Ancient Greek: The Language of Knowledge (4th Century BCE–1st Century CE)

The conquests of Alexander the Great in 336–323 BCE brought Ancient Greek to territories stretching from Greece to India. Greek — specifically its spoken form Koine — became the language of education, philosophy, and science throughout the Hellenistic period and early Roman times. Hellenistic culture spread across the Mediterranean, and even after Alexander's empire fell, Greek retained its status as the language of the intellectual elite.

Notably, the New Testament was written in Koine Greek, even though Jesus and his disciples spoke Aramaic — the authors chose Greek so their texts could be read by people throughout the Mediterranean world.

Latin: Two Millennia of Dominance (1st Century BCE–18th Century)

Latin became the lingua franca of the Roman Empire starting around the 1st century BCE and maintained this status for nearly two millennia. However, it's important to understand that even at Rome's peak, Latin remained a minority language within the empire itself. Most of the population spoke local languages, while Latin was used in administration, law, and official correspondence.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Latin didn't disappear — it transformed into the language of the Catholic Church, science, and education. Scholars from Ireland to Poland wrote their works in Latin until the 18th century. Isaac Newton published his "Principia Mathematica" (1687) in Latin.

Arabic: Language of the Scientific Golden Age (8th–13th Century)

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th–13th century), Arabic became the lingua franca of a vast region stretching from Spain to Central Asia. It was not only a language of religion but also of science: works of ancient philosophers were translated into Arabic, preserved, and expanded by Arab scholars. Words like "algebra," "algorithm," and "alchemy" remind us of this heritage.

French: The Language of Diplomacy (17th–20th Century)

In the 17th–19th centuries, French assumed the position of the primary language of international diplomacy. The court of Louis XIV at Versailles (reign 1643–1715) set the tone for European culture, and knowledge of French became mandatory for aristocrats from Lisbon to St. Petersburg. Even Russian nobility preferred speaking French — recall the characters in Tolstoy's "War and Peace."

French remained the official language of diplomacy until the mid-20th century: the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 was drafted in both French and English, marking the first recognition of equality between these languages on the international stage.

English: The First Truly Global Language (19th Century–Present)

English represents a unique phenomenon in human history. No language has ever achieved such a level of spread and influence. According to Ethnologue, in 2024 approximately 1.5 billion people speak English, yet native speakers number only about 380 million (roughly 25%). For every native English speaker, there are five people who learned it as a second language.

How English Became Global

English's rise to world language status occurred in two stages.

Stage One: The British Empire. By the end of the 19th century, the British Empire encompassed a quarter of Earth's land surface. English became the administrative language in India, Africa, Australia, and North America. Nearly 60 countries today recognize English as an official language — a direct legacy of the colonial period.

Stage Two: American dominance in the 20th century. After World War II, the United States became the leading economic, military, and cultural force on the planet. Hollywood, rock and roll, then Silicon Valley and the internet cemented English's position as the language of global culture and technology.

English by the Numbers

Sources: Ethnologue, The History of English

🌍 International Organizations

💻 Digital Presence

🔬 Scientific Publishing

English has truly become the first language that can be called global in the fullest sense. Neither Latin nor French ever achieved such reach.

The Unique Structure of English: A Language of Non-Native Speakers

English is unique in that the majority of its speakers are people for whom it is not their native language. Let's compare with other major world languages:

| Language | Total Speakers | Native Speakers | Native % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 🇬🇧 English | ~1.5 billion | ~380 million | 25% |

| 🇨🇳 Mandarin Chinese | ~1.18 billion | ~990 million | 84% |

| 🇪🇸 Spanish | ~560 million | ~485 million | 87% |

| 🇮🇳 Hindi | ~609 million | ~345 million | 57% |

| 🇫🇷 French | ~300 million | ~80 million | 27% |

Source: Ethnologue, Visual Capitalist (2025)

These figures explain a key distinction: Spanish and Chinese are languages of enormous demographic blocs, while English is a language of global communication that people learn deliberately.

The Paradox of Native English Speakers: Monolingualism

Another paradox: native English speakers are among the least multilingual people in the world.

🇺🇸 United States

Only 20–30% of the population speaks a second language

🇬🇧 United Kingdom

Only 34% can speak a foreign language; 68% of youth are monolingual

🇪🇺 European Union

75% of adults know at least one foreign language

🇸🇪 Nordic Countries

90%+ speak foreign languages; Denmark youth: 99% multilingual

Sources: Eurostat (2022), European Commission (2018), Kent State University

Native English speakers don't learn other languages because the entire world learns their language. This creates an asymmetry: for international communication, non-English speakers bear all the cognitive burden.

Challenges to English Dominance

Despite its obvious leadership, English's position is not unassailable. Two factors may change the linguistic map of the world.

The Rise of China and Mandarin

Mandarin Chinese is the language with the most native speakers: approximately 990 million people speak it from birth. The total number of speakers reaches 1.14 billion. China's economic rise stimulates interest in learning the language: by some estimates, over 100 million people outside China are studying Mandarin.

By the end of 2023, there were 496 Confucius Institutes operating in 160 countries and regions. Saudi Arabia introduced Mandarin as an elective foreign language in schools in 2024. According to Berlitz, the number of Chinese learners has grown by 25.5% over the past two years.

However, Mandarin has structural limitations. 84% of speakers are native, meaning relatively limited spread outside the Chinese-speaking world. The complex writing system (characters) and tonal nature create a high barrier to entry for learners.

As Clayton Dube of the USC U.S.-China Institute noted: "As China rises you can anticipate that more people will adopt the language. But is China going to replace English? I don't think so — certainly not in my lifetime, probably not in the next two, three, four generations."

The Technological Revolution: AI Translation

A more serious challenge to the very concept of a global language comes from artificial intelligence technologies.

AI Translation: The End of the Lingua Franca Era?

The machine translation market is experiencing explosive growth.

Sources: SNS Insider, Statista

What Can Modern AI Translation Do?

Neural machine translation (NMT) has made a qualitative leap in recent years:

📊 Scale

80%+ of global digital content requires localization — AI makes this possible at scale

🤖 Customer Support

40%+ of AI customer support in global companies is already translated in real-time

⚡ Speed

2-3 second latency for real-time speech translation

🎯 Accuracy

Up to 97% accuracy for major language pairs

Two Possible Futures

Researchers from the University of Queensland, in a paper published in PLOS Biology in June 2025, describe two possible scenarios for the future of academic (and, more broadly, all) communication:

🌐 Scenario 1: English Remains Lingua Franca

International journals continue to publish in English, but researchers with limited language proficiency write in their native language and use AI for translation. AI also helps read, review, and edit English-language papers. Knowledge continues to centralize around English, but AI lowers access barriers.

🗣️ Scenario 2: A Multilingual World

Everyone writes, reads, and reviews in their native language. AI performs real-time translation between any language pairs. English loses its status as the sole language of international communication. Knowledge decentralizes.

How AI Translation Will Change the World

If synchronous AI translation technologies achieve quality comparable to human translation, the consequences will affect all spheres of life.

Business and Trade

Language barriers have historically limited international trade. Companies were forced to hire translators, localize products, and train employees in foreign languages. AI translation radically reduces these costs.

Imagine a video conference where each participant speaks their native language, and AI instantly translates speech for all others. This is not a futuristic fantasy — this is today's reality.

Education and Science

The dominance of English in science creates serious barriers. Researchers from non-English-speaking countries spend more time preparing publications, their work is cited less frequently, and knowledge published in other languages remains invisible to the international community.

📚 The Education Gap

According to UNESCO, over 40% of people worldwide lack access to education in their native language; in low and middle-income countries, this figure reaches 90%. AI translation can democratize access to knowledge on a global scale.

Cultural Diversity

Paradoxically, technologies created primarily in English can both threaten and protect linguistic diversity.

On one hand, large language models (LLMs) are trained predominantly on English content, reinforcing English's dominance in the digital environment. On the other hand, the development of multilingual AI could give new life to smaller languages.

According to KUDO forecasts, by the end of 2025, tools supporting rare languages will increase their coverage by 50%, focusing on languages of Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America.

What Will Remain of Languages in the AI Era?

Does all this mean that learning foreign languages will become pointless? Not quite.

AI translation, for all its achievements, is still unable to fully convey cultural nuances, idiomatic expressions, and emotional undertones. A study published in the International Journal of Applied Linguistics and Translation in June 2025 emphasizes: "AI excels at processing large volumes of text and expanding language coverage, but often lacks the ability to fully grasp contextual meanings, cultural subtleties, and ethical implications."

Language is not merely a tool for transmitting information. It is a way of thinking, a window into culture, a means of building relationships. Knowing your interlocutor's language creates trust and depth of communication that no translation can provide — yet.

As Clayton Dube noted: "To speak Chinese means you begin to think as Chinese people do. You begin to understand how Chinese speakers have the world organized, how they perceive things. And that is a vital step if you're going to be culturally competent."

Conclusion: End of an Era or a New Beginning?

The history of global languages is a history of power, trade, and cultural influence. Aramaic, Greek, Latin, Arabic, French, English — each of these languages reflected the geopolitical reality of its time.

English became the first truly global language thanks to a unique combination of factors: British colonialism, American economic and cultural dominance, the Industrial Revolution, and the internet. Today, one and a half billion people speak it; it dominates science, business, technology, and entertainment.

But we are at a turning point. AI translation is developing exponentially. The market is growing at 12–25% annually. Quality is approaching human levels. Costs are falling.

Perhaps we will be the last generation for whom learning English is a mandatory condition for an international career. Perhaps our children will live in a world where everyone speaks their native language, and technology does the rest.

But this is not the end of the story of languages — it is a new chapter. Languages will live, evolve, and carry the cultural heritage of peoples. It's just that their function as lingua franca may pass to machines.